In the overwhelming majority of cases we are able to help the parties reach amicable resolution of custody issues. That ability is enhanced by our demonstrated record of fighting for the best interests of the children in those rare cases where our client’s spouse will not be reasonable. One example is the landmark case Fenslage v. Dawkins. We represented a woman of limited financial means against her wealthy in-laws. Even after our client won custody, her ex-husband refused to abide by the jury’s decision. He absconded with the children and went into hiding. When traditional law enforcement failed to apprehend him, we made aggressive use of litigation discovery to establish that the ex-husband’s parents and siblings were aiding his flight and facilitating his continued concealment. After we obtained and collected on a judgment against every family member who participated, the children were returned to our client.

-

Finer Points

-

Juries understand science.

But jurors do not value scientific evidence as highly as lawyers and experts do. To explain science effectively to jurors, trial attorneys must understand the strategies jurors use to make every-day decisions.

-

Notice how good trial lawyers bring the driest documents alive when they read them aloud.

This skill comes from practice. Try to read out loud at least 10 minutes each day. If you read your briefs and letters out loud, you will become a better writer, too.

-

Jurors know that everyone else in the courtroom is getting paid more than they are for being there, or at least they’re trying to.

Jurors will not discount expert testimony based on the expert’s hourly rate, though sometimes they may tell you that after the trial when they did not understand or believe your expert’s conclusions.

-

After you conduct the direct exam of your witness, carefully note not only the points made during the cross that must be addressed on re-direct, but also the points not scored by your opponent.

Those failed efforts may become useful in subsequent exams and in closing. Sometimes when your opponents efforts fail, he must change theories leading to inconsistent positions. Inconsistent positions, of course, undermine credibility.

-

Consider graduate students as resources to help prepare for an opposing expert.

They can often research scientific issues more efficiently than lawyers can and they bring another perspective to the review of prior depositions.

-

When lawyers make the litigation personal, they do not serve their clients well.

First, any opposing lawyer will become a very good lawyer if personally motivated. Disrespect towards an opposing lawyer often compels the lawyer to think long, hard, and often about how to win the case. Second, more time than necessary is spent fighting over matters usually resolved by agreement, which costs clients’ money, time, or both.

-

If the jurors were not paying close attention before, they will when you state in your opening “This is one of the questions you’ll be asked to answer at the end of the trial.”

Then, show them the most important liability question, and explain what evidence they will need to answer it.

-

Jurors assume that you have presented the evidence in the most favorable light for your case, and perhaps discount it a bit.

But they will not discount concessions. If you introduce unfavorable evidence, jurors will likely give it more credibility than if your opponent had introduced it.

-

Generally, pathologists and medical school professors do not make strong medical causation witnesses.

The pathologist’s skills in explaining medical issues to lay people have developed very little since medical school. Medical school professors teach medical students, not lay people. Consider clinicians who explain these concepts every day to their patients.

-

Arguing alternative damages undermines a liability defense.

The defense should argue damages only when the plaintiff is likely to prevail on liability.

-

Cases with similar fact patterns invite repetition of winning approaches.

But it is dangerous to believe that what won the last case will win the next. Begin each case with a healthy fear that what worked last time may not succeed again.

-

Objections create secrets and heighten the jurors’ attention to the offered testimony or exhibit.

Jurors form unfavorable impressions even when the court sustains the objection. Jurors are likely to form a more favorable impression when they believe your opponent is doing something inappropriate. Instead of “Objection, hearsay,” consider “Objection, the jury can’t tell if someone who is not here is telling the truth. This is hearsay.”

-

Arguing alternative damages undermines the liability defense.

The defense should argue damages only when the plaintiff is likely to prevail on liability.

-

You have heard, “Absence makes the heart grow fonder,” when a couple makes a long distance relationship work.

When it doesn’t, you have also heard, “Out of sight, out of mind.” This is hindsight bias — two statements that sound wise when looking backward. Trial lawyers defending clients must recognize this and know how to deal with it. Voir dire is a good place to start.

-

Defendants sometimes overvalue cases because they believe jurors will find liability based on sympathy for the plaintiff.

Yet time after time juries have turned away very sympathetic plaintiffs when presented with weak liability facts. If a defendant has a strong liability defense, capable defense counsel should know how to keep the jury focused on liability.

-

We believe that lawyers try all their cases, though maybe not to a jury or to a court.

Lawyers try their cases to their opponent as they proceed through discovery, pre-trial hearings, informal settlement discussions, and mediation.

-

Brainstorm everything.

Trial themes. Informal discovery. Witness exams. Arguments. Limit the brainstorming sessions to two or three others, including at least one person who is not on the case. Have a large white board or easel with notepad handy. Everyone throws out their ideas. No one argues against or criticizes an idea. Limit the sessions to 30-45 minutes.

-

When jurors select their own doctor they rarely ask, “Where did you go to medical school?”

Jurors evaluate experts based on their experience and ability to communicate, not credentials.

-

Good trial lawyers distinguish themselves from litigators by their ability to craft and tell good stories.

Clients sometimes hire the wrong lawyers for cases because they look for lawyers with extensive experience litigating a particular type of case instead of trial lawyers who know how to build compelling stories and then tell them.

-

Jurors come to court believing their task will be to decide liability.

During voir dire and openings, the plaintiffs’ counsel will try to shift the jurors to harm and money. The defense must keep the jurors focused on what the jurors first thought their task was.

-

Weaker evidence undermines your stronger evidence.

Your opponent may argue, and jurors may agree, that you believed you needed the weaker evidence to win. Use only your strongest evidence.

-

Resist doing experiments in the courtroom with your experts.

They fail too often, and the stakes are too high. Videotape the experiment under controlled conditions and have your expert walk the jury through it.

-

Action holds your audience’s attention.

Begin your stories, whether in a brief or opening statement, with people doing something.

-

You need not move in limine to exclude every misleading graphic offered by your opponent

The more egregious the graphic the greater the opportunity to show the efforts your opponent will take to mislead the jury. Use the graphic to cross examine unsuspecting opposing experts. They will either agree that the graphics are misleading or look foolish trying to justify a graphic they didn’t create.

-

Defendants sometimes overvalue cases because they believe jurors will find liability based on sympathy for the plaintiff.

Yet time after time juries have turned away very sympathetic plaintiffs when presented with weak liability facts. If a defendant has a strong liability defense, capable defense counsel should know how to keep the jury focused on liability.

-

Is Cigarette Smoking a Cause of Mesothelioma?

It is plausible that cigarette smoking could cause mesothelioma. There are many carcinogens in cigarette smoke that cause other cancers. And, historically, most people who developed mesothelioma were also smokers. Thus, there are thousands of case reports and case series of smokers who developed mesothelioma. If smoking is not a cause by itself, it certainly makes sense that it could act synergistically with asbestos to increase one’s risk of mesothelioma. Our airways are lined with cilia, hair-like structures that brush out mucus, dirt, and debris (including asbestos fibers) from our lungs. “Smoking temporarily paralyzes and even kills cilia.” Smokefree.gov.

Nevertheless, the human studies have not supported a causal association. Some found no association; others reported positive but not statistically significant associations. Recently, however, researchers in Slovenia reported a statistically significant risk of mesothelioma from smoking. Franko, et al. (2018) evaluated 150 mesothelioma cases treated at a Ljubljana, Slovenia hospital during 2007-2013, and 122 controls, who had occupational asbestos exposure (from a cement manufacturing plant) but no asbestos-related disease. The authors reported an odds ratio of 9.30 [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.83–17.98].

Does this one study prove that smoking causes mesothelioma? No. Most experts would agree that we can’t rely on one statistically significant positive study while ignoring other studies finding no association or no statistically significant association. Even when we have seemingly supportive biologic plausibility, case reports, and case series, multiple epidemiologic studies demonstrating an association beyond the play of chance are necessary to prove a causal association.

– Ray Harris

-

Are Relative Potency Analyses Proof That Chrysotile Has Some Potency for Mesothelioma?

Many researchers have published analyses of the relative potency for the commercial asbestos fiber types to cause mesothelioma. Hodgson & Darnton (2000) is often cited for estimating the potency of crocidolite to amosite to chrysotile as 500: 100: 1. Berman & Crump (2008) estimate the amphiboles were more than 200 times more potent than chrysotile. More recently, Garabrant & Pastula (2018) updated the Hodgson & Darnton (2000) analysis with data published since 2000, estimating the relative potency as 376: 83: 1. But, even if the amphiboles are more potent than chrysotile on a fiber-per-fiber basis, some argue that the analyses still show that chrysotile is potent for causing mesothelioma. And, because chrysotile was so much more widely used than crocidolite and amosite, they argue it is still a significant cause of many mesotheliomas.

Responding to this argument calls for a closer look at the analyses and, in particular, the “chrysotile” studies reviewed to find any potency for mesothelioma. It is clear that all the studies purporting to find risk from chrysotile exposure involved co-exposure to amphibole asbestos and, where the co-exposure was a likely contaminant of the chrysotile, involved cumulative exposure exceeding 100 fiber-yrs.

– Ray Harris, Erin Therrian

-

Mesotheliomas Attributed to Cell Replication Errors

Tomasetti & Vogelstein (2015) described how many cancers were not preventable. The authors purported to show that “[t]he majority of cancer is due to ‘bad luck,’ that is, random mutations arising during DNA replication in normal, noncancerous stem cells.”

Tomasetti, et al. (2017) went further. The authors examined many more cancers, including mesothelioma. They found most mesotheliomas were caused by environmental exposures, but about 34% were the result of cell replication errors. This is consistent with case-control studies, modeling using SEER data, and reported historic mesothelioma rates from time periods in the US and other countries when the rates were not likely significantly influenced by amphibole asbestos exposure.

– Ray Harris

-

The Decline in Mesothelioma Rates Continues

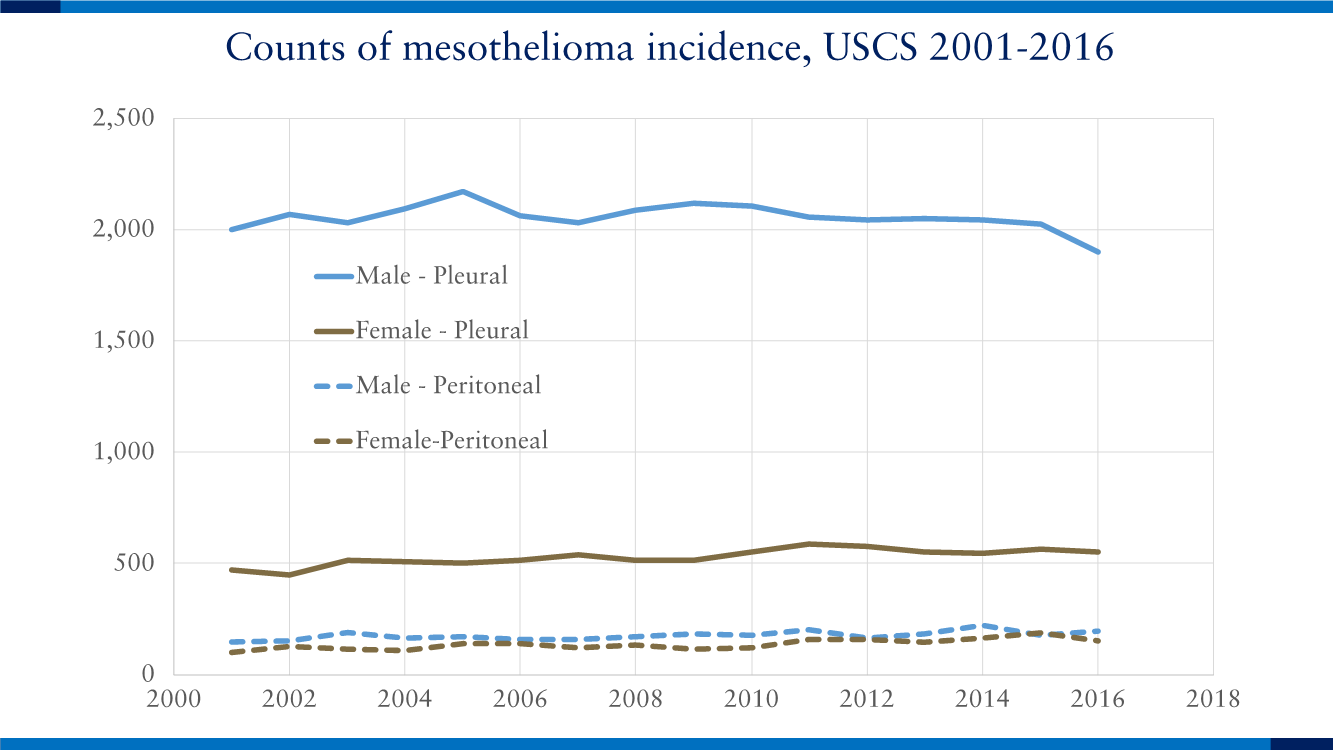

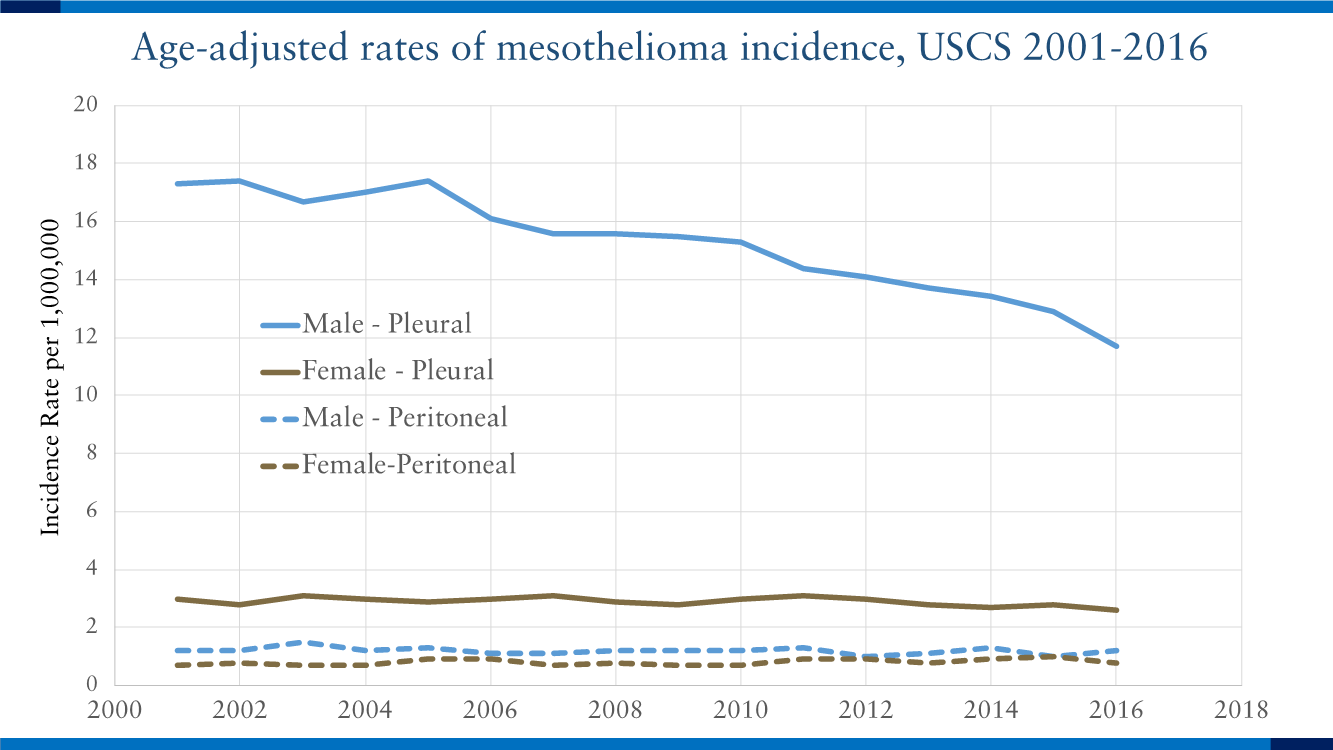

The US Cancer Statistics reflect data reported by the SEER registries and the National Program of Cancer Registries. Combined, these two programs provide 100% coverage of cancer incidence in the US since 2001. The statistics show that the actual yearly counts of pleural mesothelioma cases in men have remained relatively flat.

But, as the population has increased, the age-adjusted rate in men has dropped by almost one-third since 2001.

Meanwhile, in women, both counts and age-adjusted rates of pleural mesothelioma have remained relatively flat. The same is true for peritoneal mesothelioma in both men and women. This supports the view that peritoneal mesotheliomas and pleural mesotheliomas in women are not associated with asbestos exposure.

– Ray Harris

-

Risk of Mesothelioma in the North Carolina Textile Cohort Quantified

Loomis, et al. (2009) described the incidence of mesothelioma and lung cancer in four North Carolina textile plants. In the plants denoted as plant 1 and plant 2, there were no mesotheliomas or pleural cancers. There were three pleural cancers in plant 3. In plant 4, the authors reported four mesotheliomas and one pleural cancer among the workers.

With regard to the nature of the exposure at the plants, the authors reported: “According to available records, only chrysotile was used except for a separate operation in plant 3, where a limited amount of amosite was carded, twisted and woven between approximately 1963 and 1976.” Thus, the pleural cancers in plant 3 workers cannot be attributed to chrysotile.

But this paper also has been cited as proof that chrysotile caused the mesotheliomas in plant 4. Available evidence rebuts that argument.

Plant 4 was owned by Johns Manville during the 1960s. Our research at the Manville document repository revealed evidence that UNARCO previously owned plant 4 and that it made amosite blankets for the Navy as well as crocidolite valve packing. Our deposition of a co-author of the article confirmed that the authors had not checked the repository for information about the products made in plant 4 before publishing their article.

The authors and others have published follow-up papers on these textile plants. Elliot, et al. (2012) estimated the mean cumulative exposure for three of the plants. The authors’ mean cumulative exposure estimate for the plant 4 cohort was 147.5 fiber-years.

Loomis, et al. (2019) pooled the data from plants 1, 3, and 4 and quantified the risk of pleural cancer and mesothelioma. Figure 2 of the study indicates that a substantial portion of the workers experienced more than 1,000 fiber-yrs of exposure, and many experienced more than 4,000 fiber-yrs of exposure. Adjusting for age, race, and year of follow-up, the authors reported no statistically significant increased risk of pleural cancer or mesothelioma at 100 fiber-yrs of exposure with a 10-year lag. Adjusting only for race and length of follow-up, the authors were able to calculate a slight increased and significant risk of pleural cancer (1.15) for 100 fiber-yrs of exposure, but the risk was not doubled until after 500 fiber-yrs of exposure.

– Erin Therrian, Cary Schachter, Ray Harris

-

Mesothelioma Diagnoses on Asbestos Workers’ Death Certificates Are Often Wrong

Many occupational cohort studies rely upon the cause of death listed on death certificates for assessing cancer. Yet this information is often not accurate. See, e.g., Wissing, et al. (2019); Tan (2019). This is particularly relevant when assessing mesothelioma incidence.

Boffetta, et al. (2018) illustrates the potential for misclassifying mesothelioma. The authors “searched medical and pathology records and specimens for 127 workers from a textile asbestos factory in Italy who died during 1963-2013 with a diagnosis of pleural or peritoneal neoplasm or mesothelioma on death certificate, to confirm the diagnosis with immunohistochemistry (IHC) markers.” The authors were able to confirm only a small proportion of mesothelioma diagnoses: “The diagnosis of mesothelioma was histologically confirmed for 35 cases (27.6%); 5 cases were classified as non-mesothelioma (3.9%), for 33 cases a mention of mesothelioma was found on record but no sufficient material was available for revision (26.0%); no records were available for 54 cases (death certificate-only 42.5%).”

This “study shows that for a relatively large proportion of members of historical cohorts of asbestos workers, the information on pleural or peritoneal cancer/mesothelioma reported on death certificates cannot be validated through medical or pathology records, and even less so with review of pathology material.”

– Ray Harris

-

Juries understand science.